Battle of Pharsalus

| Battle of Pharsalus | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of Caesar's Civil War | |||||||

|

|||||||

|

|||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Populares | Optimates | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Gaius Julius Caesar Mark Antony |

Gnaeus Pompeius Magnus | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| Approximately 22,000 legionaries, 5,000-10,000 Auxiliaries and Allies, and Allied Cavalry of 1800 | Approximately 40,000-60,000 legionaries, 4,200 Auxiliaries and Allies, and Allied Cavalry of 5,000-8,000 |

||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 1,200 | 6,000 |

||||||

|

|||||

The Battle of Pharsalus was a decisive battle of Caesar's Civil War. On 9 August 48 BC at Pharsalus in central Greece, Gaius Julius Caesar and his allies formed up opposite the army of the republic under the command of Gnaeus Pompeius Magnus ("Pompey the Great"). Pompey had the backing of a majority of senators, of whom many were optimates, and his army significantly outnumbered the veteran Caesarian legions.

Contents |

Prelude

Pompey and much of the Roman Senate fled Italy for Greece in 49 BC to prepare an army. Caesar, lacking a fleet, solidified his control over the western Mediterranean — Spain specifically — before assembling ships to follow Pompey. Pompey had appointed Bibulus to look after his fleet - ordering him to destroy any of Caesar's ships that he came across. However, before this plan could be implemented, Bibulus died of fever. This allowed Julius Caesar to land his troops at Pharsalus. Caesar thereafter marched overland through southern France, blockading Massilia (present-day Marseille), and managed to assemble a small fleet. After crushing Pompey's forces in Spain, Caesar focused once again on Pompey and his troops in Greece. Pompey had a large fleet, as well as much support from all Roman provinces and client states east of Italy. Caesar, however, managed to cross the Adriatic in the winter, with Mark Antony following a little later because Caesar lacked sufficient ships. Although Pompey had a larger army, he recognized that Caesar's troops were more experienced, and could prove victorious in a pitched battle. Instead, Pompey waited Caesar's troops out, attempting to starve them by cutting off Caesar's supply lines. Caesar made a near disastrous attack on Pompey's camp at Dyrrhachium and was forced to pull away.

Pompey did not immediately follow up on his success. An indecisive winter (49–48 BC) of blockade and siege followed. Pompey eventually pushed Caesar into Thessaly and urged on by his senatorial allies, he confronted Caesar near Pharsalus. Caesar began the battle with a smaller, but veteran, force. Pompey's troops were more numerous, but far less experienced. Moreover, Pompey's senatorial allies disagreed with Pompey over whether to fight at Pharsalus, and pushed Pompey, who wanted to starve Caesar's soldiers, into a quick decision.

Caesar had the following legions with him:

- Legions of veterans from the Gallic Wars – Caesar's favourite legion, X Equestris, and those later known with the names of VIII Augusta, IX Hispana, and XII Fulminata

- Legions levied for the civil war – legions later known as I Germanica, III Gallica, and IV Macedonica

However, all of these legions were 'short', and did not have the requisite numbers of troops. Some only had about a thousand men at the time of Pharsalus, due partly to losses at Dyrrhachium and partly to Caesar's wish to rapidly advance with a picked body as opposed to a ponderous movement with a large army.

Battle

Deployment

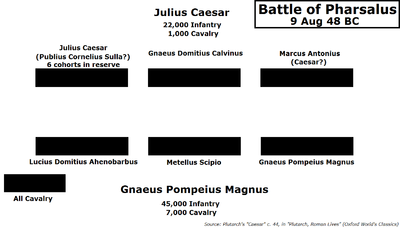

Pompey deployed his army in three lines, 10 men deep. He posted his most experienced legions on the flanks (the first and the third legion on his left with Pompey himself commanding, the Syrian legions in the center with Scipio the Cilician legion and the Spanish cohorts on the right with Afranius), dispersing his new recruits along the center. In total, Caesar counted 110 complete cohorts in the Pompeiian army, about 45,000 men. Pompey also placed 600 horses on his right flank toward the River Enipeus, a natural barrier that protected the wings of both armies. He had give the command of the cavalry to the lethal Labienus, the former commander of Caesar's favourite X legion. He deployed the rest of the army on his left together with his auxiliary troops. His main battle plan consisted of an effort to push back the numerically inferior Julian horses and then attack the enemy from behind. Pompey had disclosed his plans to his companions days before the battle, and Caesar became aware of them. His plan was to allow Caesar's infantry to advance and charge the cavalry to meet Caesar's outnumbered cavalry and then destroy his infantry.

Caesar also deployed in three lines. He arrayed his men 6 men deep. He rested his left on the marshland of the river and he positioned all his cavalry on the right, against Pompey's squadrons. Behind them he hid light troops, carrying javelins and other weapons. Caesar himself commanded the cavalry. He also had 2,000 legionaries as reserves. He posted the notorious tenth legion on his right under Sulla, with the understrength eighth and possibly the ninth on his left under Antonius. In the center he designated Domitius as the commanding officer. According to his accounts, he had 80 cohorts on the battlefield, about 22,000 men.[1]

Conflict

Pompey ordered his men to not charge the enemy, but rather to patiently await until Caesar's legions came into close quarters. This he did by the advice of Caius Triarius, expecting the enemy to fall into disorder having to cover double the expected distance. Although critical of Pompey's decision, Caesar praised his men's discipline and experience, since they stopped their charge halfway of their own accord, to regroup and catch their breath, before completing the charge.

When the lines came in close contact, Labienus ordered his cavalry to attack, at first successfully pushing the Caesarian horse and starting to flank the legions. It was then that Caesar ordered his cavalry to move away. The first line of the Pompeiian horses saw the infantry ready with the javelins and panicked. They turned their backs and this resulted in confusion.They fled exposing their right flank. The cohorts slaughtered the enemy light troops which supported their cavalry, wheeled towards the enemy, and attacked them from the rear. To further pressure his opponent, Caesar ordered his, as yet uninvolved, third line to relieve the front ranks. The remaining Pompeiian soldiers knew that their game was up and decided to flee and soon the battle was won.

Pompey retreated to his camp and ordered the garrison to defend it. Caesar urged his men to end the day by capturing the enemy camp, and they complied with his wishes, furiously attacking the walls. The Thracians and the other auxiliaries who were left in the camp, in total seven cohorts, defended bravely, but they were not able to fend off the enemy assault. Pompey fled with a very small retinue, claiming that he had been betrayed. Caesar had won his greatest victory.

Aftermath

Pompey fled from Pharsalus to Egypt, where he was assassinated on the order of Pharaoh Ptolemy XIII. Interestingly enough, Ptolemy XIII sent Pompey's head to Caesar in an effort to win his favor, but Caesar was not pleased about receiving the head of his son in law in a box. It was even said that Caesar cried. Nor did Ptolemy, advised by his regent, the eunuch Pothinus and his rhetoric tutor Theodotus of Chios, take into account that Caesar was granting amnesty to a great number of those of the senatorial faction in their defeat, men who once considered him an enemy. The Battle of Pharsalus ended the wars of the First Triumvirate. The Roman Civil War, however, was not ended. Pompey's two sons, the most important of whom was Sextus Pompeius, and the Pompeian faction led now by Labienus, survived and fought their cause in the name of Pompey the Great. Caesar spent the next few years 'mopping up' remnants of the senatorial faction. After finally completing this task, he was assassinated in a conspiracy arranged by Marcus Junius Brutus and Gaius Cassius Longinus.

Importance

Paul K. Davis wrote:

"Caesar’s victory took him to the pinnacle of power, effectively ending the Republic."[2]

Battle date

The date of the battle is given as 9 August 48 BC. This is according to the republican calendar. The date according to the Julian calendar, however, was either 29 June 48 BC (according to Le Verrier's chronological reconstruction) or possibly 7 June 48 BC (according to Drumann/Groebe). Pompey was assassinated on 3 September 48 BC. The point is not entirely academic; had the battle taken place in the true month of August, when the harvest was becoming ripe, Pompey's strategy of starving Caesar would have been senseless.

Location

Controversy long raged among scholars over the location of the battlefield. Although the battle is called after Pharsalos, four ancient writers - the author of the Bellum Alexandrinum (48.1), Frontinus (Strategemata 2.3.22), Eutropius (20), and Orosius (6.15.27) - place it specifically at Palaepharsalos. Until the early 20th century, unsure of the site of Palaepharsalos, scholars placed the battle south of the Enipeus or close to Pharsalos (today's Pharsala). The “north-bank” conjecture of F. L. Lucas (Annual of the British School at Athens, No. XXIV, 1919-21), based on his 1921 solo field-trip to Thessaly, is now, however, broadly accepted by historians.[3] “A visit to the ground has only confirmed me,” Lucas wrote in 1921; “and it was interesting to find that Mr. Apostolides, son of the large local landowner, the hospitality of whose farm at Tekés I enjoyed, was convinced too that the site was by Driskole [now Krini], for the very sound reason that neither the hills nor the river further east suit Caesar’s description.” John D. Morgan in his definitive “Palae-pharsalus – the Battle and the Town” (The American Journal of Archaeology, Vol. 87, No. 1, Jan. 1983), arguing for a site closer still to Krini, writes: “My reconstruction is similar to Lucas’s, and in fact I borrow one of his alternatives for the line of the Pompeian retreat. Lucas’s theory has been subjected to many criticisms, but has remained essentially unshaken.”

Named after battle

The battle gives its name to

- Pharsalia, a poem by Lucan

- Pharsalia, New York, U.S.

- Pharsalia Technologies, Inc.

References

- ↑ Julius Caesar, Commentarii de Bello Civili,III

- ↑ Paul K. Davis, 100 Decisive Battles from Ancient Times to the Present: The World’s Major Battles and How They Shaped History (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1999), 59.

- ↑ Sheppard, Simon, Pharsalus 48 B.C.: Caesar and Pompey - Clash of the Titans, Oxford, 2006

Further reading

- Gwatkin, William E., Jr. (1956), "Some Reflections on the Battle of Pharsalus", Transactions and Proceedings of the American Philological Association 87: 109–124

- Caesar's account of the battle